An Atlas of Collapse: The Climate Crisis

I want to address the climate crisis first out of all the aspects of collapse because, while it is in many ways far more abstract than the other issues we're facing, it is still an emergent and all-encompassing problem. Climate change is going to increase food scarcity, force millions to flee their homes, and cause trillions of dollars in damage and loss of profits in the coming years. All of these factors feed into everything else because, say it with me: the climate crisis is a threat multiplier.

Almost across the board, climate scientists are growing increasingly alarmed–it is probably an understatement, actually, to say they are just alarmed. Climate change is accelerating, we're already experiencing severe damages from what warming has already occurred, and we are unsure just how high temperatures may go. While we at When/If are not ones to cleave to the IPCC, as I tend to think their conclusions are watered down, even they are showing signs of extreme despair, and raising warnings that make my neckhairs prickle. Of those scientists surveyed by the Guardian in the above link, the majority agreed we would see at least 2.5C° of warming. This amount is more than enough to upend tipping points, effectively ending the world as we know it.

Before we go for the broader picture, I want to start local. Since we in the United States are coming up on summer, we are entering a climatically active time of year during which a lot of us could suffer for a lack of preparedness. We have severe weather to worry about (my city, for instance, has had three tornado-warned storms so far this year), heatwaves, and hurricane season a few months away. So let's start with a little guidance before we get into the meat and potatoes.

Above-Average Heat

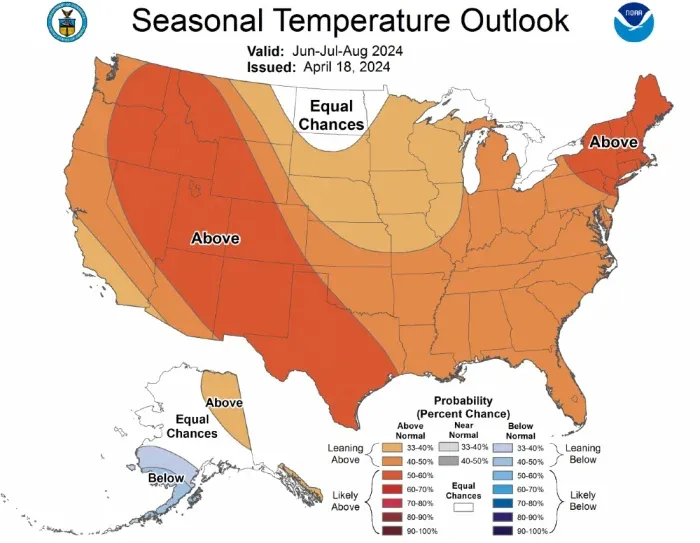

This summer the heat is expected to be much like a chipper young nerd: irritatingly above average.

This map predicts our summer heat in fashion not too dissimilar from how our general climate outlook is forecasted years out: a generalized increase in heat across much of the United States with particular increases in the South and Southwest. And if we're consistently beating the average, the average stops being that–so this is where we're headed forever, and ever-upwards.

It may not seem like much, but as I've said before with respect to winter temperatures: every degree counts. In southern states, some of these temperatures are reaching the upper thresholds for agriculture, meaning that a heatwave could decimate harvests. And as we eke higher and higher, these single degrees matter for simple living, too. Last summer, you'll recall, communities in Arizona saw temperatures so high that falling on the pavement meant receiving serious burns. Edging higher on the world's thermostat means that these sorts of conditions will spread, eventually, across the country. And, remember, hot air holds more moisture–meaning there is more potential for devastating rains and storms.

Beating this heat is no simple task, particularly in the sorts of scenarios we're frequently talking about, like blackouts. Without electricity, the upper reaches of summer heat are simply deadly. Refer to previous letters about heat for further guidance. In brief: you need air conditioning at these temperatures. How you get it and how you help others with it is the real question.

Rain and Shortages in the UK as Portent

There hasn't been a "dry" period in the UK for almost 18 months, and those last 18 months have seen a record-breaking amount of rain. This rain has severely impacted farm output across pretty much every sector: it has been difficult to plant potatoes, wheat, and other crops; those crops that get planted often do poorly in the soggy soil, or outright rot; the rains have killed off newborn lambs, and cows have not been able to graze, resulting in reduced milk production.

To make matters worse, there have been heavy rains and droughts (simultaneously!) across much of Europe and Africa, resulting in reduced yields there as well. Economists have warned that food prices, as a result, are going to increase. Wholesale prices for potatoes, for instance, have increased by 60% year over year, per the above linked article. That's a real blow to a staple crop. Farmers, agriculture experts, and economists are calling this situation untenable.

Dr. Paul Behrens, an associate professor of environmental change at Leiden University in the Netherlands, said: “We should all be extremely concerned … I expect huge turmoil and escalating prices in the next 10 to 20 years. When food prices spiral we always expect political instability. I wish people understood the urgent climate threat to our near-term food security.

That's an appropriate response. We are going to be facing ever-worsening crises, and this is just the beginning. While the United States is less likely to be impacted in the way the UK has due to, simply, a massive size difference and diversity in climates, it does not mean that such an impact is far off.

AMOC Slowdown and Sea Level Rise

Through 2000-2020, AMOC has slowed down by 12%. More accurately, one measured portion of AMOC slowed down, but. This is alarming. If it only took 20 years for AMOC to slow down that much, we can only imagine it will slow further, and faster, in the coming years. And I think we're beginning to see some of the knockoff effects of AMOC slowdown/stoppage already.

The rate of sea level rise for the Gulf of Mexico has risen more steeply than most of the world's coastlines. Along with that, portions of the US East Coast are also rising quickly. Now, rising on the Gulf is not directly tied to AMOC, but the East Coast is. This sea level rise, at first glance, may not seem like a lot–what's 7 inches? But it's 7 inches over ten years–matching rise over the last fifty. If that rate keeps up–and I don't see why it wouldn't if it doesn't rise faster–that's well over a foot in twenty years. This is the sort of thing the IPCC would tell you we could expect in the coming decades, but it's here now.

With this rise comes a lot of damage. Coastal wetlands are being inundated with seawater, "drowning," as the link above puts it. These wetlands are crucial buffers, funnily enough, against storm surges. If and when these wetlands die off, cities further inland will be hit far harder by hurricanes that, by most measures, are getting stronger faster. In addition, the world loses a valuable carbon sink and a robust ecosystem bites the dust.

In addition, coastal cities are experiencing severe impacts to their infrastructure. You may recall the seawater intrusion in the Mississippi River last year that threatened to overtake New Orleans' water supply. Imagine this, plus overloaded sewage systems and flooded roadways, and on a bad day you've got people potentially trapped in homes that are without water, surrounded by disease-spreading sewage. And recall that those bearing the brunt of these disasters, first and worst, are communities of color, who have been purposefully pushed into these positions and who continuously receive less support.

Last note on this: it's worth mentioning that rather than face climate change head-on, we are going to instead spend money on symptom infrastructure that is itself ultimately doomed. Tide walls, pumps, levees, sand banks–none of these will last. That's not to say that we should make no effort in saving communities at risk, but it is to say that our governments will willfully ignore the writing on the wall; and, of course, these aforementioned investments will go to cities and regions with residents who could afford to leave in the first place.

If You're Just Joining Us

This crisis has been bearing down on us for a long while, but we have entered, in the last few years, a period I think we can agree is the beginning of a new reality for the world. This is going to hurt, and it's going to get worse. And worse.

We survive this, even improve lives, by banding together outside of traditional power and economic structures. We begin by ensuring we, personally, are prepared for danger. That means shelter, water, and food, secured for at least several weeks time. This carries us through acute disaster. From there, we expand–not just our own reserves, but into our communities. We make peace with neighbors, break bread with them. Share food, share books, share ideas. Help them with their chores. Shovel their walks in the winter. They will bring skills to the table you don't have, and know people who will add further. Until you have a community capable of saving itself.

It sounds easy to just say it. It's not. We're not exactly wired for this, in the US. But we have to get there. If it weren't work, I probably wouldn't have to write a newsletter about it.